- Home

- Elizabeth E. Wein

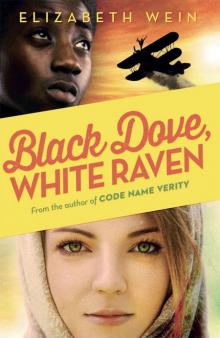

Black Dove, White Raven Page 3

Black Dove, White Raven Read online

Page 3

‘We made you a story this time. Em thought of it and I drew it. Look, Black Dove and White Raven have got a moving bed – it is under a tent that the wild ponies are carrying on their backs. Look at this bed the ponies are carrying!’

Momma liked to look at our stories. She liked the Black Dove and White Raven Adventures. But then she’d get mad at me because I kept using Delia’s gorgeous clothes for dress-up. It was OK for Momma to float around the house in Delia’s silver kimono, for some reason, but not for me.

‘Look, Em, can you just keep your nose out of Delia’s things for a little while?’ Teo scolded me. ‘’Cause every time I think Momma’s going to start talking to us again, you turn up wearing Delia’s earrings and then Momma does nothing but cry for two days. You are not helping.’

And I stopped. It was hard, but I really did. Grandma used to give us scraps of rickrack and buttons to make up for it. Teo made me a pair of White Raven wings. They’re not actually raven wings, but American goldfinch wings, the flashiest bird we could think of. I brought them with me to Ethiopia and I still wear them sometimes, unless we’re going out on a feast day when it makes more sense to blend in.

‘You just have to be careful with Momma for a while,’ Teo told me. ‘She’s broken. Like a jug with a broken handle that you try to glue back together. It looks all right, and it’ll hold water. It’s still a good jug. But you’d better not ever pick it up by the handle. You have to wait for the glue to dry, and even then it still might not hold.’

I squinted at him. ‘Come again?’

‘You know what I mean. Momma is that broken jug. And Delia is the handle. Just keep out of Delia’s things.’

‘How come she likes our stories when we draw them, but she doesn’t like to see us act them out?’

‘She can pretend it’s her and Delia when we draw them,’ Teo said. ‘She can put herself in the story when she’s listening to it. But if she’s watching someone else all dressed up, it isn’t her.’

One day Momma followed us down to the kitchen when we went to make her coffee. It was about a month after the Bird Strike and her face was still bruised – she was all yellow around the eyes. She sat at the kitchen table in Delia’s cream silk pyjamas with the pink shell pattern and read Freckles out loud to us all morning.

When Grandma came in from the stables at lunchtime, and we were all sitting there with the coffee pot still on the burner and all the coffee boiled away and none of us had noticed, Momma looked up at her and complained, ‘Mother, can we send these kids to school so they can figure out how to read to themselves?’

Grandma swept the coffee off the stove and then swooped down on Momma to kiss her on top of her frazzled gold hair.

‘First thing in September. Oh, Rhoda, I’ve just been waiting for thee to ask.’ She always says ‘thee’ to her daughters and to us, old-fashioned and familiar, because she is a Quaker. ‘Does that mean thee’s going to stay home for a while?’

‘No place else I’m planning to go.’

That is when we really became the new Black Dove and White Raven, when we began making up their Adventures.

When we first started we just drew everything, like comic strips, because we didn’t know how to write. Some of those pictures were pretty weird. We decided that Black Dove (Teo) could make himself go invisible, and White Raven (me) was a glamorous master of disguise. So sometimes we’d just draw Black Dove’s equipment, like a plane that looked like it was flying without a pilot, or a runaway train he was stopping. (Teo gets carried away making up interesting-looking planes and trains.) And there are no pictures of White Raven that actually show her because she is always in disguise.

We drew a lot of these stories, but we also acted them out. We specialised in reunions and rescues. Every episode ended in celebrations with real cake and bunting in the kitchen or the barn, with Grandma and Connie and Sallie the housekeeper usually dragged in as party guests. Everything always came out all right in The Adventures. We cranked out happy endings like we were starving for them. Well, I guess we were starving for happy endings.

School was an endurance exercise that brought us back to reality five days a week. The only good thing about it was learning to write, which was what made The Adventures of Black Dove and White Raven really take off. Teo was the only black person in our class in New Marlow, Bucks County, PA, but there were also a couple of black kids who were sisters, one in the class ahead of us and one in the class behind. There were two teachers for the whole school, the Misses Larson, who had done their first teaching in prairie schools in the Dakota Territory just after the railroads were built. They weren’t as old as you’d think because they’d started when they were not quite sixteen. Now that I’m not quite sixteen myself, thinking about the Misses Larson makes me feel 1) uneducated, 2) unemployed and 3) old.

The Misses Larson were good teachers, but not so good at figuring out what was going on in the playground. There were always a couple of mean kids who called us names. They picked on Teo because he was black, but also because he always managed to end up covered with dust whenever he went to the chalkboard, or paint if we were painting, or he’d come in from recess with twigs or spiderwebs in his hair from climbing in the mulberry tree at the edge of the schoolyard. They picked on me because everybody thought Momma was a crazy woman. They locked up your ma yet? She grow wings yet? Bet you have to tie her up at night so she won’t fly away. Hahahahahahaha.

And this is in the place Delia complained was too nice to be real.

So Teo struggled not to be noticed and I pretended to be somebody else all the time and here’s the kind of thing we’d end up doing.

‘Those rats with the spitballs are waiting behind the steps again,’ Teo pointed out as Miss Ida Larson rang the bell to announce that recess was over. We had to lurk between the fence and the mulberry tree for the whole dinner hour so no one noticed us. We’d been at the New Marlow School for two months. ‘They do it every Friday after lunch. Do they think we’re nitwits?’

‘They do it on Friday because they know Miss Larson will forget about it over the weekend,’ I answered. ‘Let’s just not go back in. No one will notice.’

‘What’ll we do instead?’

‘Whatever Black Dove and White Raven would do. Fly someplace interesting.’

‘We can’t fly,’ Teo said practically. ‘How about we take a train! We can pretend we’re rescuing people on the Underground Railroad.’

‘You mean go somewhere? Not just stay here in the schoolyard but actually leave?’

‘Sure! What’s the difference to Miss Larson if we’re here or home or anywhere else? Can you find the river? ’Cause those big trains go by with open doors all the time. We could get off at Lambstown and meet Connie after school and she could bring us home on the trolley.’

We knew about the Underground Railroad because Grandma’s Quaker mother had actually run an Underground Railroad station in Philadelphia, a safe house for runaway slaves going to Canada through Pennsylvania. We didn’t know it wasn’t a real railroad. We imagined secret trains running without lights in the middle of the night.

‘That might be your best idea,’ I exclaimed.

‘Grandma won’t think so, but Connie won’t tell,’ Teo said with confidence.

So I led us through the woods to the railroad bed by the Delaware River, and after about twenty minutes of climbing around on the rocks below the embankment, meeting up with our imaginary runaways, we heard a train coming and scrambled back up to the tracks. Three engines creaked past at low speed in a cloud of steam, followed by at least a hundred wooden freight cars. They were going so absolutely painfully slow that anyone would be tempted to climb in, and when one of them came along with an open door and an iron running board, it just looked too easy.

Teo hesitated. I did not. It was easy. (We were lucky that day; we did it about half a dozen times in three years and it was mostly hair-raising. But we never got caught.)

‘Come on, Black Dove! No one can

see you!’

He laughed with delight. I am always pretending to be White Raven right out in the open, but he is sort of shy about pretending to be his made-up hero, and it tickles him when you treat him like that’s what he really is. I held out my hands, but he took a running jump and hopped up next to me without any trouble. The car was full of empty bushel baskets and feed sacks. We sat side by side in the open door with our feet dangling, rattling through the wet-smelling fall woods at about five miles an hour.

‘No one can see me, but you need a disguise,’ he said. ‘Grab one of those sacks when we get off.’

After we hopped off at the other end we spent an hour under the steel-girder bridge at Lambstown weaving orange and yellow maple leaves into the feed sack for a Swamp Angel disguise (we got that name from Freckles, but improved on its meaning). We discussed the perils of ending up chained in a jail cell, which we didn’t really think would happen to us, but which was no doubt going to happen to Black Dove. Teo managed to lose his cap and tear his sweater. Connie was not too thrilled to see us at her trolley stop, I remember, but she softened up when we told her she was rescuing us from slavery. I guess she felt the same way we did about the New Marlow School, even without people slinging names and spitballs at her.

Aw, writing that essay for Miss Shore is just making me want to work on The Adventures. This pilfered theme book is a great disguise for when I get fed up with doing school work. Remember the story where White Raven became a bareback rider in the circus, so that she could distract the owners while Black Dove freed all the bears? That episode was a direct result of the Drummond sisters’ riding show on our first Thanksgiving at Blue Rock Farm. I don’t want to forget that, either, just like I don’t want to forget Delia.

All Momma’s sisters and their husbands and their babies (two very new, two just walking) came to stay for Thanksgiving the year of the Bird Strike, and they decided to do a circus in the riding school for me and Teo and the babies. They always did this on Thanksgiving when they were little, and they hadn’t all been home together for five years. They were excited about having an audience. Even Momma came out to watch. She didn’t bother to get dressed, but she put on her old leather flying coat and her tall boots because it was cold, and covered her head with a blue silk scarf of Delia’s. She looked a little strange, but at least she was there.

Except for Connie, the aunts’ show was pretty tame because they were so out of practice, but Aunt Lorna and Aunt Jean did a really funny clown act – pushing each other and falling off horses and jumping on backwards and stuff like that. Aunt Connie was fabulous and scary – she made all the other aunts crouch down in a row on the ground and got her horse Jasper to jump over them.

Grandfather had a fit. ‘You girls all get off the ground – make it snappy!’

The aunts didn’t pay any attention. They weren’t at all scared. Afterward, when Connie trotted back to where we were all watching by the rails of the gate, all her big sisters defended her.

‘She’s the best part of the show!’

‘Connie’s the starlet!’

Momma was quiet until she said, ‘Connie, take those stirrups off.’

Connie shot her big sister a startled, excited glance and Momma gave that one quick, steady nod.

Connie seemed to know what it meant. She slid like melted butter from Jasper’s back, handed the reins to Aunt Alice and started to unbuckle one of the stirrup leathers. Aunt Jean sauntered over to help with the other stirrup while Alice lengthened the reins. Momma took her coat off and stood in the chilly November air wearing nothing but Delia’s pretty silk pyjamas and her riding boots – and then she took off her boots too. She wasn’t even wearing socks.

‘Rhoda!’ Grandma scolded. ‘Thy feet!’

Momma rolled her eyes.

‘Thee knows I have to do it barefoot, Mother. Jeannie, come on. Make me a step.’

Aunt Jean laced her fingers together and Momma put one naked white foot into the cup of Jean’s hands, and then she vaulted up into Jasper’s saddle.

She had the lengthened reins bunched up in one hand, and she leaned forward and wound the fingers of her other hand through Jasper’s mane, and Jasper started trotting, very neat and brisk. Momma got up on her knees, still crouched forward. I recognised what she was doing. It was exactly the way she crouched on the fuselage of an airplane, bent forward and hugging the plane with her knees, exactly the way she’d crouched behind me on that day Delia had tied me and Teo together in the cockpit of their new Curtiss Jenny.

Jasper trotted around the school with Momma kneeling barefoot on his back, the pink-and-cream silk pyjamas fluttering in the breeze. Momma urged him into a canter.

The aunts must have known what she was going to do. Grandma and Grandfather too, but me and Teo didn’t have an inkling. Even though we’d seen Momma wing walking a thousand times, even though we knew that’s what she did best, that she got paid for it – even though we’d sat in a plane and watched her while she did it – neither one of us ever in a million years guessed you could ride a horse the same way you could ride an airplane.

Jasper cantered smoothly around the ring. My jaw dropped as I watched Momma pull one knee up and then the other, planting her feet squarely across the saddle, gripping with her toes. She straightened her knees, still holding on to Jasper’s mane, so that she was nearly standing, bent over double, like a ballerina touching her toes. Then she let go of Jasper’s mane, lengthened out the reins and stood up.

Jasper just kept on cantering. And there was Momma standing barefoot on his back, her arms spread for balance, straight as an arrow, with the blue silk scarf pulling free of her hair and the silk pyjamas billowing around her lanky body like a circus costume.

It was the most amazing thing our momma had ever done, and that’s saying something.

She let Jasper canter around the ring twice while she stood careless and proud on his back. Then she knelt back down and sat. She let him trot around back to me and Teo, where they both stopped short.

‘Oh, Momma, I want to do that!’ Teo cried.

He scrambled through the rails and she bent over with her arms held out to scoop him up. All the grown-ups let out yowls of protest.

‘Don’t you do it, Rhoda –’

‘He only just started riding –’

‘You’re too thin! You won’t be strong enough to hold him!’

She hoisted Teo up in front of her.

‘Jiminy Christmas. What a bunch of nervous Nellies.’

Then she trotted away from us around the school.

Everybody shut up after that, because they didn’t want to scare her – or Jasper – or Teo.

Momma pulled Teo’s shoes off and tossed them against the fence. She didn’t stand up again herself, but she helped Teo to stand up. Momma had her arms around him the whole time, even though she wasn’t touching him – just making a protective circle with her arms. And I know he was the safest person in the whole world with Momma’s arms around him like that.

Teo didn’t smile; he was concentrating. His eyes were fixed somewhere far in the distance. He hardly wobbled. He’d never done anything like that before, something that made everybody look at him. Nobody would call him a daredevil because he’s not a show-off. But when he fixes on something he likes to do, he sure can be full of surprises. I haven’t ever been so proud, or so jealous, of anybody in my whole life as I was of Teo right then. Black Dove is supposed to be invisible.

They went around the ring twice, just like Momma had done, this time with Teo standing and Momma sitting behind him with her arms in a ring around his body. Then she made Jasper walk again, and she swept Teo tight in a hug. Then she started to cry against the back of his neck.

She didn’t ever do it again. We went a little bit crazy trying to get someone else to help Teo do it, but no one else would. The one thing we were absolutely not allowed to fool with on our own was the horses, so we never tried it ourselves.

We both sort of wish we had.

>

I am not going to show any of this to Miss Shore. I will have to start again.

‘Home Is Where the Heart Is’ by Em M.

(Or ‘How We Ended Up in Ethiopia’)

Momma met Papà Menotti because she went to Italy to be in the Army Nurse Corps during the Great War. Grandma and Grandfather were not happy about it. They didn’t want her to be involved in a war at all, even helping to fix people. They are Friends – Quakers. They don’t believe in going to war. So Grandfather was mad at Momma, but it is a known fact that she’s his favourite girl and he will let her do anything she gets her mind stuck on – standing on a cantering horse, marrying a soldier, flying a plane, taking her children to live in Africa.

So Momma was a nurse and Papà was a pilot for Italy and his plane crashed and he was picked up by the Americans. Momma ended up taking care of him and then falling in love with him. After the war she brought him back to Pennsylvania just long enough for them to get married, and then he took her to France with him because he had a job as an instructor at a flying school there. He hired Delia to go along with them to France as Momma’s maid because Momma was going to have a baby (me).

Of course Momma had never had a maid. Grandma and Grandfather are always working in the stables and the riding school, and they hire men to help them. They also hire an old Pennsylvania Dutch woman to cook for them and do the housework, but Sallie never waited on Momma and her sisters when they were little, and she used to yell at me and Teo if we didn’t make our own beds. For darn sure Momma never had anyone around who was just there with nothing else to do but fill the tub for her and comb her hair and carry her shopping bags. And if you knew Momma, you would know that 1) she hates water, 2) she bobbed her hair herself when she was thirteen so she wouldn’t have to take care of it and 3) if she ever went shopping, nobody was going to carry her bags but Momma herself.

But there wasn’t really anything for Momma to do in France except take baths, comb her hair and go shopping. So she and Delia did it together. After not very long they were buying things for both of them – they’d get matching hats and fur collars for their coats. They’d sit drinking coffee together in parks and cafés and practise their French. Momma had learned some in high school, but Delia didn’t know any till they got to France. They’d go see moving pictures together. And they could, because nobody cares in France if black and white people go around together, especially if they are both pretty young women.

The Pearl Thief

The Pearl Thief Cobalt Squadron

Cobalt Squadron The Empty Kingdom

The Empty Kingdom Code Name Verity

Code Name Verity Rose Under Fire

Rose Under Fire A Coalition of Lions

A Coalition of Lions Black Dove, White Raven

Black Dove, White Raven The Winter Prince

The Winter Prince The Sunbird

The Sunbird